Visualization and the Power of Abstraction

Code Blocks as… Blocks

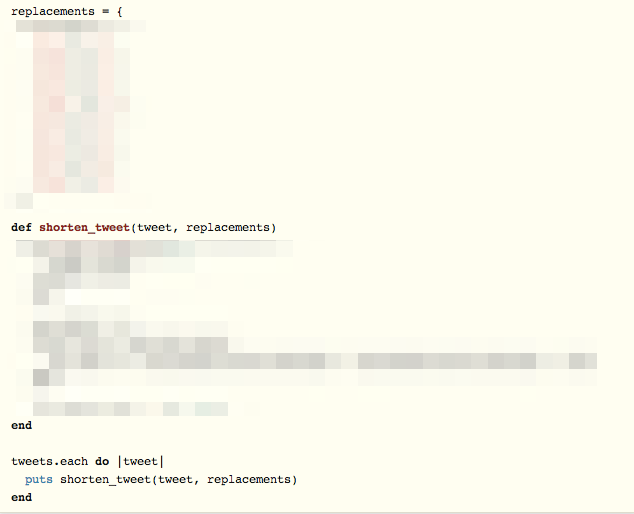

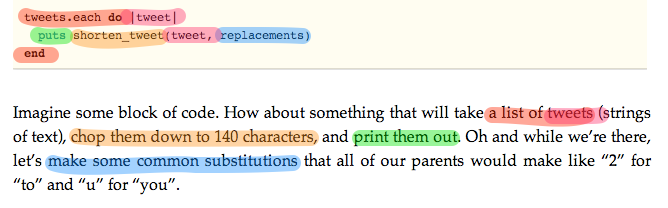

Imagine some block of code. How about something that will take a list of tweets (strings of text), chop them down to 140 characters, and print them out. Oh and while we're there, let's make some common substitutions that all of our parents would make like "2" for "to" and "u" for "you". Looks kind of like this right?

Cool, so you already understand the power of abstraction. We don't really care how we can shorten a tweet, just that we can shorten a tweet. This allows us to really focus on what our program should be doing, and not on how it is doing it. Luckily, Ruby code reads really nicely and pretty clearly shows us what we are doing:

So we can see how our logic got translated to Ruby code. The great thing here is that each highlighted section is also an abstraction. We don't really know or need to know how iteration works with ".each". Just like we don't really know or need to know how text gets printed on the screen. We just see "puts" and imagine a big green blob of code that Ruby uses somewhere to handle printing to the screen.

Let's just sharpen that method up a bit for a second and see what's going on:

def shorten_tweet(tweet, replacements)

if tweet.length <= 140

return tweet

end

new_tweet = []

tweet.split().each do |word|

new_tweet << (replacements[word.downcase] ? replacements[word.downcase] : word)

end

new_tweet.join(' ')[0, 140]

end

What does knowing how this method operates (poorly) really tell us? Nothing! The implementation isn't really all that important at this step of the process. All we need to know is we can shorten a tweet with "shorten_tweet".

So the code does this, that, and the other thing. Once again, what does this code block do? That's right, the exact same thing it did before we understood how it was doing it.

Like, Let It Go

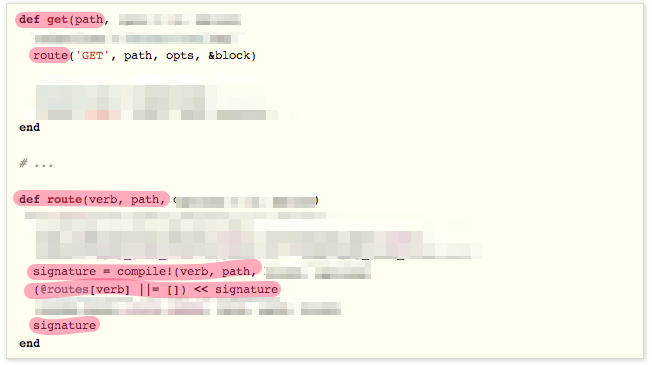

This was a contrived example, the code was simple enough for us beginner programmers to follow. Now imagine the following code block:

def get(path, opts = {}, &block)

conditions = @conditions.dup

route('GET', path, opts, &block)

@conditions = conditions

route('HEAD', path, opts, &block)

end

# ...

def route(verb, path, options = {}, &block)

# Because of self.options.host

host_name(options.delete(:host)) if options.key?(:host)

enable :empty_path_info if path == "" and empty_path_info.nil?

signature = compile!(verb, path, block, options)

(@routes[verb] ||= []) << signature

invoke_hook(:route_added, verb, path, block)

signature

end

Whoa, that's crazy! Look at all those abstractions that the writers of Sinatra know! How can we ever figure this out? Well, we can look for some key areas - the method definition, the return value, calls to other methods that we might be more familiar with.

So there are probably a few key pieces in here that deserve more attention. The "get" method basically seems to delegate to the "route" method. It seems to create a "signature", which might be important because it is a return value later. It also adds the signature to a list of routes that it is maintaining in an instance variable.

It still does the same thing, whether we really understand it or not.

We frequently run into code that is over our heads, even in libraries and applications that we use every day. The important part is to sometimes let ourselves trust those that maintain the code, instead of worrying about all the details ourselves.

8 "Bit" Brain

I have heard from very reliable sources (people talking) that the brain is really only capable of storing about 8 substantial pieces of information at a time, give or take a few. There's just no way that we could manage to keep all the information relevant to our program in our head at all times, especially as our code bases grow to thousands and thousands of lines of code.

By allowing our brain to group logical pieces of information via abstraction, we free up more space for working on the next piece. It is of course possible that one of our "pieces" behaves unexpectedly - we might have to jump down the "rabbit hole". Just when we are going for that major context switch, we can keep in mind to break the problem down into smaller pieces and abstract them together to build up a whole understanding of the system.